What does reconciliation mean to me?

What does reconciliation mean to me?

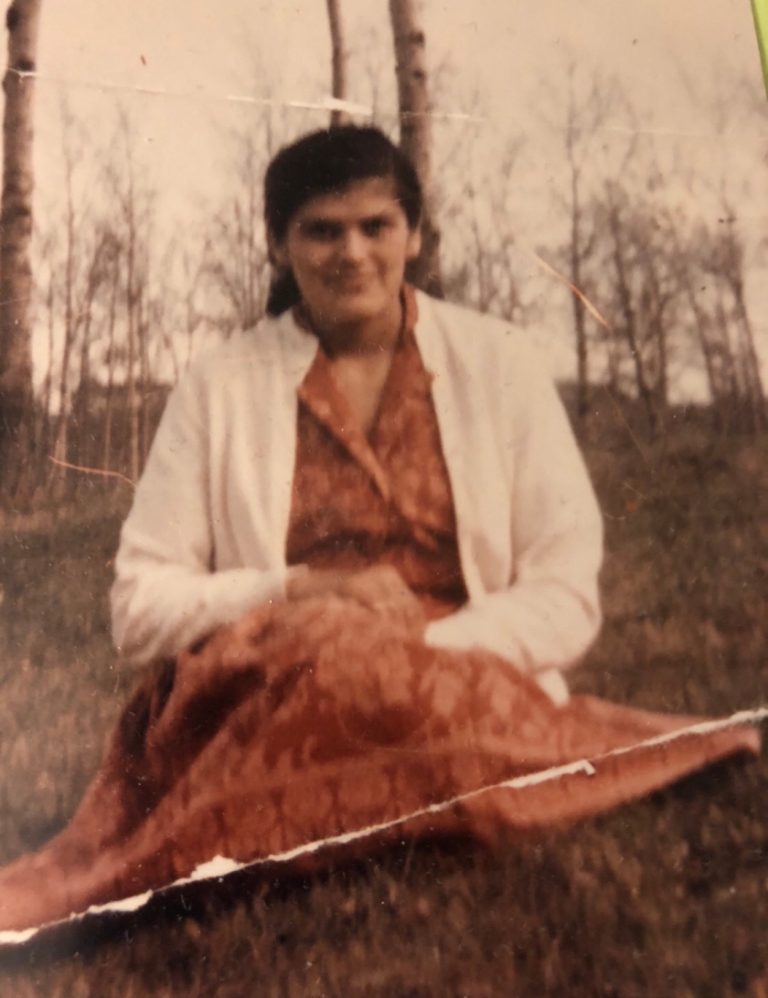

This is a photo of my mother, 21 years old, taken at Emily Murphy Park in Edmonton in the fall of 1962. Fifty-five years later we celebrated my father’s 90th birthday there June 3, 2018.

I have written many blogs sharing pieces of how I see the world through the healing journey that I continue to walk. I often share two perspectives, one being what I felt or thought or lived and then the lesson learned from an event or period of my life.

I facilitate a number of sessions for both indigenous learning and mental health learning and they are often treated as very separate topics. However, as an Indigenous woman and through all my life experiences, education and career, and now with the push on “Reconciliation” in the government I see reconciliation as healing for all people. I do not see healing as an ‘Indian only issue’ but as a means of reconciling history of all Indigenous groups or people.

I am finally ready to share the story of my mother through my eyes. I was never discriminated for being part white, I was always discriminated as a child for being an Indian and this had a significant impact on all the decisions I have made in my life. Right or wrong, the decisions I made were to never repeat what I lived or to become that cycle of abuse that permeates so many Indigenous families and communities. My father raised his children to be proud of our Indian heritage. It may have hurt us all but 50 years later what he once knew has become true: we would all be OK.

So now I share with you “My Mother’s story through my EYEs”

“My sister was just a baby when they met. My mother an Indian woman, from the far north, lived at a time in Canada when being an Indian was seen as no good. Even with changes to the Indian act – those who looked Indian were overtly discriminated against for many reasons but mainly based on what people believed or thought, never on the truth. I was conceived in the winter / spring of 1961 and began my journey with my mother long before we would meet each other face to face. She loved me and was happy she would have my father’s baby and so she moved with my father 1300 kilometers South. Away from family, friends, and a way of living she thought she was happy to leave behind. She was going to be a white woman in a white world because she was a white man’s wife or so she thought; and so her story begins, as I know it.

I wrote a paper in 2006 of the phenomenological description of my mother, who will not be offended by this personal portrayal, as she has been passed on now for more than 30 years, but lives close within my heart. This version of that paper is an edited story version which is an attempt to describe two very vivid images I have of my mother; my earliest memory of her near the start of my life; then twenty years later, at the end of her life. The images of these two periods are, in my opinion, polar opposites, with extreme contrasting behaviors that probably perpetuated the seemingly different personalities I saw in my mother. There are a multitude of scenarios that appear to have contributed towards a possible array of psychological disorders, which ultimately led to my mother’s untimely death. Note that this is my story and my interpretation of the life I lived. My father and siblings, and others, may have their own interpretation.

In the beginning, I remember my mother as this beautiful Indian Princess, whom I thought was the most beautiful woman in the world. She was my mother and I was going to be every bit as beautiful and grand. She had jet-black hair, thicker than molasses, and smooth, glowing, blemish-free, olive brown skin. She walked with grace, confidence, yet was modest and in charge of everything she commanded. She was simply beautiful and, I would do anything she wanted just to be near her, basking in her presence. What I did not know in my four brief years of life was that, my mother was a mere 24 years old with five children under the age of five. There was my older sister who was five; my next two younger brothers were three and my youngest brother was just two. The three year olds were not twins; my parents adopted a baby boy who one week older than their baby boy. In another four years, my parents adopted another baby, this time a baby girl, increasing their family to 6 children. Everyone who knew my mother, knew not to challenge her – my father accepted the additional responsibility.

During this youthful adult time, my mother was very much in control of her own personal life. She was the fourth child of nine children and the first female; therefore, a lot of responsibility fell on her. Her father and older brothers worked the trap lines that their homestead was built on in Aklavik, NWT, along the Mackenzie River. My mother’s mother had T.B. and was institutionalized for much of my mother’s youth. My mother, at the age of 12, and with a grade 6 education, had to quit school so she could care for her five younger siblings. In addition, she had to care for and prepare meals for her father and older brothers. At the age of 16, my mother’s father died, and the next day her grandmother also died and, within a very short period of time of these two significant deaths, my mother’s remaining family was relocated by the government to a small place called Inuvik. During this period of time in her life, government Agents and residential schools controlled Indians. Drinking alcohol was a means to escape their miserable lives; in 1952, the Indian Act had just been revised to help assist Indian people, instead of eliminating them. However, my mother would experience harsh discrimination up to the day she died.

The move to Inuvik was a huge shift for my mother, who was raised along a trap line and taught a way of life in nature. As a family, she was taught to follow the caribou during summer months, pick berries, smoke fish and dry meat. She moved to a town where this way of life was stripped from her family and, a life of boredom; chronic consumption of alcohol became the norm for many relocated Indians, which then lead to both violence, physical and verbal abuse. My mother’s way out was to hook up with a white man passing through either with the army or for work, with the hope of marrying him and moving South so that she could declare herself a non-Indian and raise her children in a white man’s world.

The radiant woman whom I adored, as an innocent child, turned into a witch from hell by the end of her life. Her once beautiful, jet-black hair was dry, unkempt, damaged and streaked with greasy, grey strands. Her long, elegant legs were tree stumps, laden with an obese body full of bulging veins; feet rough, ugly and full of large corns and calluses, from being uncared for and being pressed into too tight, cheap footwear. Any joy or happiness she may have had at one time in her life left her, and she now wore a vacant look, staring past you into space. Her smile was gone, the weight of the world hung heavy around her neck. There was no hope – worry and loneliness were her only friends. The friends of past years left, they no longer liked to drink or associate with such a mean spirited woman who was angry at the world, angry at her husband and hateful towards her children. The misery of her life was seeping through her pores and out of the soul of her eyes. There was no knowledge or memory of dancing or smiling or children’s laughter or even the simple smells of good food cooking.

Through all this scheming and dreaming, never did my mother expect the discrimination she encountered could be responsible for leading her sorrowful being into a pit of despair and such an abysmal existence. After moving south with my father, my mother’s first encounter with brutal discrimination was the day of my birth. The Charles Campsell was the Indian’s hospital for the North and, my mother was to give birth to me at this hospital, where she would be among other Northern Indians whom would be her comfort and support during this special event. Heavy into labor, she arrived at the hospital only to be greeted and turned away from her “home away from home.” They sent her to the white man’s hospital where she felt the pangs of hatefulness by people who knew nothing of her life. She was lonely and alone in a world she did not know, with a new baby and a body recovering from an exhaustive feat. At home, my mother enjoyed caring for my older sister and me. She also had made friends with a German-speaking couple who also were being shunned by ignorant and ill-informed individuals. With the arrival of my three brothers, my mother’s full time work very quickly evolved into round the clock childcare. With five young, demanding, whining, curious and needy children, one of whom was inconsolable, my mother often was sleep deprived, resulting in irritability and a proneness to emotional explosiveness.

When she was rested, drinking socially, or calm after a violent, raging outburst, she was extremely remorseful, quiet and accommodating. This passive behavior often led to frustration, anger and, eventually, vengeance and out-of-control rage. As six small children, we often huddled together to protect one another yet, when my mother was calm, we all craved her tiny bits of affection.

My mother, along with her children, returned to the North so that she could have the support and aid of her family. She still ventured into the world of drinking occasionally. My father drank, her brothers drank, her mother and sisters drank and so she joined the rank and file. By the time we moved south again to Fort Smith and Hay River, the occasional drinking became a weekend ritual. No matter where we lived, Northern family and friends were around and drinking was the social norm for the adults, while many children ran around unsupervised. At the age of 25, my mother and father decided to return to Edmonton to raise their family. We had a mobile home that was destroyed enroute. My parents were without insurance and so they then began their life together in Edmonton living in a motel for nine months, before finally being able to rent the top floor of a house. Northerners, traveling to or through Edmonton, stayed with us, regardless of where we were living. Everyone drank, smoked and partied endlessly in our home. From our small two-room unit in the motel to our five room top floor of a house, the scene was always the same, quarters cramped with many people. It was rare to be at home with less than a dozen people around. My mother was forever cooking; cleaning and raising northern indigenous foster children as well as her own children. Raising children, who had the appearance of looking ‘Indian’, whatever that means, was difficult for my parents, especially my mother. School authorities often called chastising my mother that her Indian children were bad, lazy, and useless savages. We were repulsive to have in a predominantly ‘white’ school.

As no formal training was required, my mother eventually took work at a hospital as a Nurse’s Aid. She worked the night shift because by the age of 30, she rarely slept at night, the result of sleep deprivation coupled with insomnia. When she arrived home in the mornings, she would see us off to school and then try to sleep during the day. When she couldn’t sleep, she resorted to whatever array of prescription pills she had. Medical doctors fed her pills because she was not wanted in their professional affluent offices. She often accompanied the pills with a shot or two of rye or vodka, hidden in her bedroom closet. She did have good days and, on her good days, our home would be clean and smelling fresh, our clothes would be laundered, and the smell of good food lingered in the air. On those not so good days, my mother could be found slumped in a chair, or on the floor sleeping. If she was not at either extreme, she was miserable, irritable, easily frustrated and angry. She would then snap at anything, everyone walked on eggshells. Her level of anger determined how violently we were beaten or yelled at. Ironically, the beatings were often more comforting than the verbally abusive slanders. The beating could be as mild as washing one’s mouth with soap to blisters arising from floggings with a belt. She sometimes made it into her bed and then she would sleep until it was time to wake for her night shift.

As my mother’s personal caregiver, I was responsible for ensuring her uniform and all accessory clothing, namely underwear, hose and shoes were cleaned and polished. I had to iron her uniform, put in the buttons and then, 30 minutes before calling her a cab, I had to wake her, dress her, do her hair and get her into the cab and on her way so that she would make it to work on time by 11:00 pm. As her bad days increased, my responsibilities as caregiver, homemaker and prep cook increased. When my mother’s friends arrived on weekends that usually started on a Thursday evening, by the age of 10, I became the bartender because I could mix the best drinks, with more alcohol than mix. I was successful at getting people drunk so that they could pass out, leaving me to resume my miserable life until the next fight broke out, the police were called or the whimpering of a child being beaten or abused, yet again, diminished.

Authorities of any sort were insensitive and unsupportive towards my mother. If police were called to our home, they often ignored us because we were Indian or they were very clear on letting my mother know that we were not worth their time. She was an Indian with Indian trash children. She wanted to improve her education and was verbally assaulted for making such a request. The adult educational system was not intended for her, as an Indian person, it was meant for the privileged white world. She wanted to be white but the common people saw her for whom she was, her brown skin color meant Indian, which meant “no good.” There were no available resources or support for my mother. She often felt lonely, defeated and angry. She drank to forget, and then she forgot why she drank. She mixed prescription drugs and alcohol to numb her spiritual and psychological pain, and then she forgot why she was in pain. She beat us kids to alleviate her pain and then she was remorseful for hurting us. On her good days, my mother was kind and caring. Sundays were always set aside for visiting at the Charles Campsell hospital. She took time to visit people from the North, bringing them candy, smokes and magazines. She let us attend with her and we played outside while she visited. On Sundays, we were never beaten and it was the one-day we always looked forward to for many years.

My mother wanted to change her life but the desire to be in pain and find relief from pain was stronger than the desire to change. She had no friends, her husband left her, her children rarely visited her, her home was now a desolate and crumbling, ugly dwelling. All the windows were shattered. Whiskey bottles were shattered and left stuck to the floor where they were used for target practice for guns and throwing things. The furniture was damaged and broken, the house a constant mess. Outside, the grass was dead, the fence had fallen and weeds had taken over where plants used to grow. There were animal feces in the yard; the garage was a storage place for weekend partiers flying high on street narcotics. The fruit trees no longer produced and the other trees were dying due to their use as urinal stands. My mother was no longer able to cook for herself or the multitudes of family who were passing through. The state of her health was a mirror of the state of the home we grew up in. Her health, mind and behavior fell apart, unhealthy and disgusting to view. Red swollen eyes, tattered hair, unnourished skin, cracking and splitting finger nails, edemas hands and feet, sore joints from carrying around excessive weight, red face, stench seeping through her pores, slurred and jumbled speech, incoherent thoughts, unfocused attention, glazed stare and an inability to measure time. Her diet was unhealthy, fatty and unmemorable, even though she was a Type II diabetic. Her eyesight had deteriorated and her vision was blurred yet she would not consider seeing a doctor. Her blood pressure was skyrocketing and the little pills were ineffective. She drank her alcohol with any type of prescription drug, over the counter drug or illegal drug, anything for the rush and a moment of non-existence. The diet pills wouldn’t take the weight off; she was no longer able to hold down a job; folks in the church she attended wanted nothing to do with her, and she was no longer able to make new friends.

She watched the world from her one room apartment. She was alone and her attempt to stop the drinking was unsuccessful. In its final stages, her body was infused with a jolt of adrenaline, speeding up for a fleeting moment. Then it halted abruptly and she was dead. She succumbed to the blues, her misery and her unbearable loneliness – she died of a shattered broken heart . . . . .

I miss the woman I idealized my mother to be. I was too young to understand the horror the federal government’s actions took on my mother and her life. Beauty comes with strength and courage; my mother’s intentions were to give her children a better life than that of an Indian. She wanted to continue her education but she was turned away; she wanted to eat in restaurants with my father and they were turned away; she wanted the best for her children and we were turned away. Instead, without compassion and understanding from the society around her, she lost that good intent and turned into a monster. I miss the Indian Princess image of my mother, of my childhood youth. I am not certain what the diagnosis would be for a tortured spirit consumed by the psychological and physiological abuses, of an ignorant society.”

Thank you for sharing your time reading this story. My mother meant the world to me and I always wanted her to be well. I understand substance abuse now as a chronic illness and can see how much it destroyed her. Just like any debilitating illness, alcoholism is no different. I can also see now so clearly the intergenerational PTSD and complex grief that permeates Indigenous families and communities. Although I stopped the cycle of substance use and violent physical abuse, it would be years before I stopped all abuse, such as the yelling and screaming. To an untrained person they would not know how challenging it is for someone living with past trauma doing the best they can.

What has changed in 50 years is acceptance and resources. There are so many more resources especially in urban cities, for Indigenous people to access. Elders and Indigenous centres are available, even if under funded. Many people in the various First Nations, Metis Nations and Inuit Communities heal coming together to share their stories, ceremonies, and foods; or they work together to build / create traditional clothing, crafts and tools. Within these communities all people are invited to participate and learn Indigenous cultures and traditions. Reconciliation to me is about healing together.

Through this reconciliation many people who were abused or tortured or spiritually destroyed have learned to forgive, mostly themselves, then found the love within to love those who harmed their spirits. Experiences are shared in books, in meetings, at gatherings … sharing stories is also a means of sharing knowledge and helping others who also are finding ways to heal. People will not forget their past, but they will let go of the emotional connection that made them so sick and often stuck. Healing helps us replace the negative vibes with healing compassionate loving vibes.

The more I talk about my mother and write about my experiences the more I return to seeing the woman of love and beauty I knew as a young spirit. She found peace in dying and she is the mother who looks out for children from wherever she is. She taught me to be the mother I wanted and loves me every day of my life.

What does reconciliation mean to you?

With much love and kindness, Alexis.